Issue #11 | Excerpt, "Real Sugar is Hard to Find"

AS SEEN IN PLANET SCUMM ISSUE #11

WRITTEN BY SIM KERN

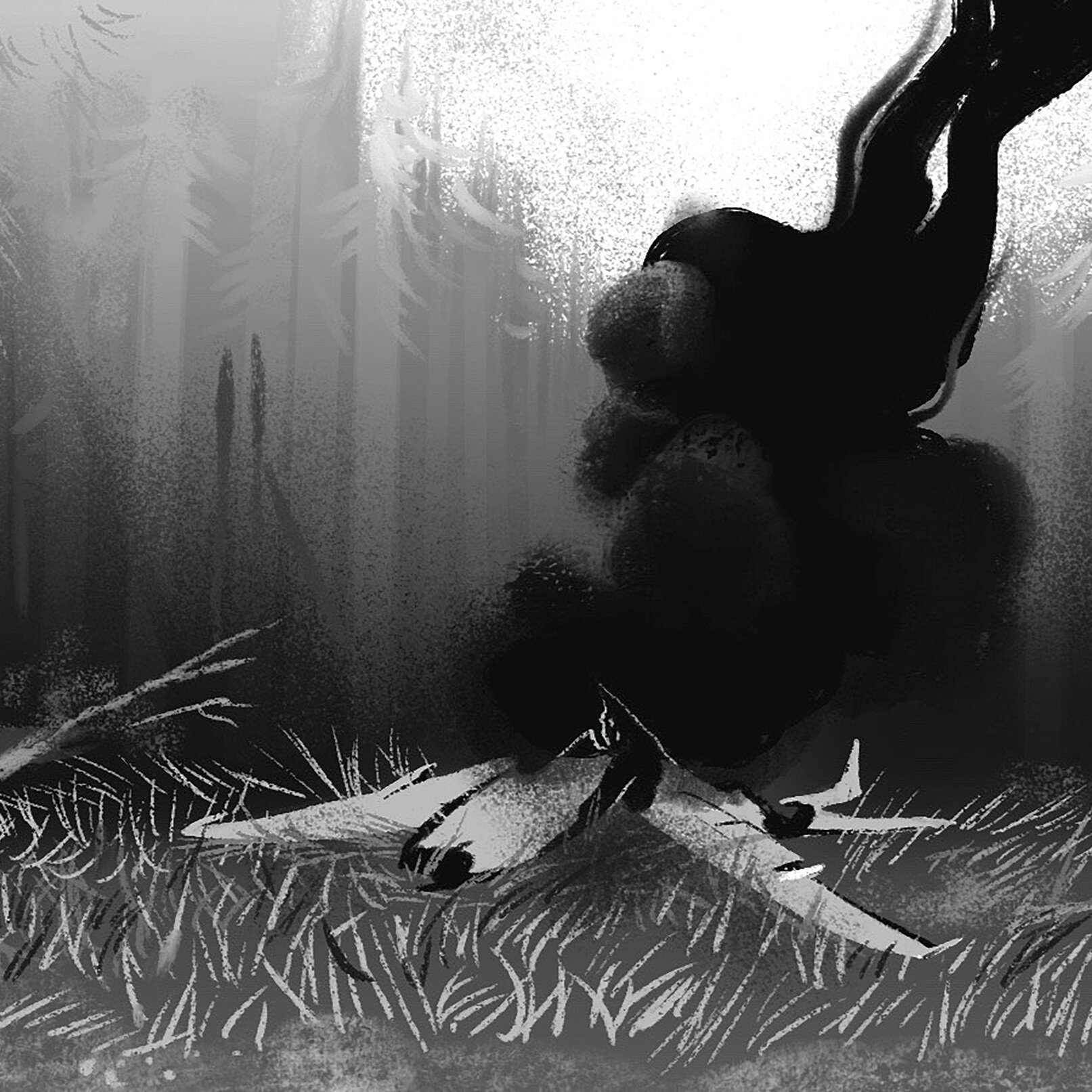

Illustration by Maura McGonagle

Mom has to chat with everyone in the store, bragging about our cake adventure like it’s some charming, twentieth-century game, not a ploy to convince her suicidal daughter to go on living. Our neighbors nod and smile, giving her as little encouragement as possible to keep talking. They all know about Nicholle and Dad. So much tragedy for one little family.

By dome standards, it’s indecorous, and our neighbors—particularly their kids, shifting their weight next to their parents, checking their Lenses to avoid making eye contact with me—are all desperate to get away from us. But mom is oblivious to the way she grates on others, and it takes fully an hour to get out of there.

By the time we get back in the car, my patience is already threadbare, and we haven’t even left the dome. At the western airlock, she tells me to put on my respirator while we’re still in the plastic tunnel, but I ignore her. Guardian drones buzz above the clear-cut land that stretches for half a mile around Fox Haven Dome, their bullets held at bay only by the transmitters embedded in our palms. I don’t relax into my seat until they’ve disappeared around a bend in the road.

“So are you going to tell me where we’re going, or am I supposed to drive around until I hit a goat?”

Mom snorts a laugh, then taps the air a few times, and a location appears inside my Lenses. I swipe my hand to send it to the car’s nav system but decline the auto-pilot. The roads where we’re going will be too full of potholes for the AI to manage. I’m surprised Mom’s willing to venture so far from our dome. I’ve only been to that area once, to this show at The Granary. The bands had all sucked. I’d only gone in hopes of seeing Mahim, but he didn’t show up.

The highway out of Fox Haven is lined with skinny, teenage trees. There’s a pattern to the foliage—apple, pine, maple, pear—some configuration determined by scientists to maximize food production and carbon reclamation. It repeats at quarter-acre intervals, giving anyone speeding by an unsettling feeling of déjà vu. Dark swoops among the branches could be wild birds or the flying drones that guard the AG company’s investments from scavengers.

After a few miles, we hit a patch of younger forest, and the horizon opens up, broken by dozens of glinting domes. But straight ahead is Old Waukesha, which isn’t domed. I stop at the first traffic light, where a few people huddle in a bus shelter. A toddler in a stroller tugs on their respirator. Their parent isn’t wearing one, nor are the two teenagers leaning their heads together in a way that makes me ache for Mahim.

Mom sinks deeper into her seat, and she taps the passenger panel to arm the car’s surface taser.

“Seriously?”

“Sweetie,” she sighs. “Do you know how many car jackings there’ve been here in the last month?”

“No. How many have there been, exactly?” I ask.

She huffs. “Way too many.”

“Whatever. You’re so domeist. You realize this town is all just, like, families, right? Families trying to get by, do the best for their kids, just like you?”

“Peter, I’ve lived in this town all my life. I don’t need a lecture on it from my own son.”

The light turns green, and I pull forward. Main Street is lined with two-story brick buildings, the windows all wrapped in patchwork plastic sheeting to keep out the plain air.

“When my grandmother was a girl, this town was bustling. That was the big theater, where she’d see flat-vids for a quarter. And she always talked about the fountains full of soda.”

I’ve heard this spiel literally every time we’ve driven through this town since I was five years old. I don’t know why, but it makes me want to claw out my own eardrums.

“When I was a girl, though, Waukesha was a ghost town. Everyone had moved out to housing developments, and the stores went bankrupt because people shopped online. But then a few years before you were born, Congress declared the War on Warming. Domed communities were just popping up, and I insisted we buy a house in one. Your dad didn’t think it was necessary, but good thing we did! Domeless property all got seized and turned over to AG Corps for reforestation, and the domeless had to crowd together in these abandoned downtowns.” She clucks her tongue. “Shame that the architecture is ruined by all that plastic. So much history in these buildings. I wish they could get it together and put a dome over Waukesha.”

“It’s not that simple, mom. There’s no work for them. The system is, like, set up to keep them domeless.”

“Oh? And what ‘system’ is that, exactly?”

I’m not sure how to explain it, but I know I’m right. Mom takes my silence for victory and smiles. I try to remember how Mahim explained it—something about the racist-classist-domeist praxis. But thinking about Mahim makes my heart lurch, and my mind go gooey, and all I can remember is kissing him that night at the Gorge, when we stayed up talking until the sun rose out of the lake.

My stomach wrenches, and for the millionth time, I regret not asking for his Handle. We could’ve been chatting on our Lenses this whole month, but I was worried about looking too eager. I’d said, “See you around,” and I was sure I would—at the next silo show or abandoned-mall rave. But he’d disappeared from the scene, and now I had no way of talking to the one person in the world whose presence didn’t make me feel more alone.